Wis 11:22-12:2; 2 Thes 1:11-2:2; Luke 19:1-10

This year’s readings of the later parts of Luke’s gospel has left me thinking often: these stories are exceedingly weird. Who really prays, “Thank God I am not like those BAAAD people over there”? Who really imagines a son wishing his father were dead so much as to take his inheritance? Who really wants to heed the severe story of the rich man and Lazarus, even if someone HAS risen from the dead? On the surface, the stories are distressing to our tidy sense of how the world is supposed to operate.

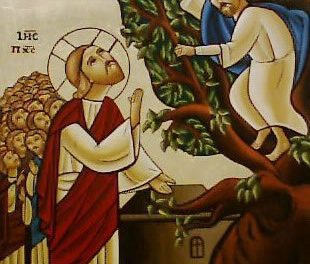

So it may be with relief that we get to hear the tale of Zacchaeus, a “chief tax-collector” whose curiosity about Jesus results in a house visit and a declaration of an active, ongoing giving of half of his possessions to the poor. Half, we think relievedly – at last, we are not hearing yet again about leaving all possessions! And Zacchaeus seems a likeable outcast: a short but energetic tree-climber.

Luke Timothy Johnson, however, suggests a more challenging reading of the story. He juxtaposes it with the story of the wealthy young ruler, offered by Luke a few verses before. Johnson suggests that read together, the stories suggest that “appearances can deceive” – for the rich young ruler practiced piety from his youth and went directly to Jesus seeking an answer about eternal life, whereas Zacchaeus appeared unrighteous and wouldn’t go to Jesus directly. Yet Zacchaeus is the one who receives the prophet, and who in addition is ready and willing to practice free generosity with his possessions. Johnson reminds us that one’s use of possessions is a chief mark of genuine discipleship in Luke’s gospel. But more importantly, the stories read together suggest that we should be ready to find openness to Jesus in unexpected places – and closedness in unexpected places, too. Like many other of these distressing Lukan stories, the moral is: some who are first will be last, and those seemingly last will be first.

Today’s first reading puts this paradoxical design in beautiful perspective, by saying:

Before the LORD the whole universe is as a grain from a balance

or a drop of morning dew come down upon the earth.

The imagery suggests delicate hand-craft, down to the smallest detail; the sage goes on to suggest that God’s mercy extends to everything that God has made, down to the smallest detail. God leaves nothing and no one out as He journeys, but as we are reminded throughout these gospels from Luke, there is a single hindrance: fullness! Being full of possessions or full of yourself leaves no perspective from which a person is able to receive and wonder at God’s tremendously gracious care for all he has made. It is this expansive solidarity, found in and through faith in Christ’s and Christ’s proclamation of the Kingdom, that Luke criticizes again and again, from every angle.

NOTE: This post originally appeared in a slightly different version on this blog in October 2016.