In an editorial, “Sometimes the death penalty is warranted,” in the Washington Post, Charles Lane observes that Anders Breivik, who murdered 77 people in Norway on July 22, 2011, declared that the maximum possible sentence for his action–21 years in prison or longer if certain conditions are met–is “pathetic.” The death penalty, which Norway abolished years ago, Breivik instead “would have respected.” As an editorial in America notes, however, “the citizens of Norway remain firm in their opposition to the death penalty. A poll conducted after the shootings found that only 16 percent of Norwegians were in favor of capital punishment.” While Lane expresses his respect for this principled moral stance against the death penalty, he nevertheless thinks there is a problem with outlawing capital punishment for all cases in nations like Norway and in 17 U.S. states, with Connecticut being the latest to do so.

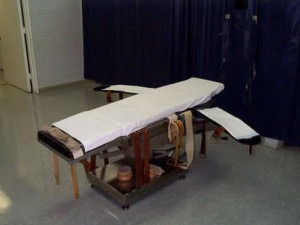

This 2004 file photo from the Virginia Department of Corrections shows the execution gurney at the Greensville Correctional Center's death row in Jarratt, Va.

Lane acknowledges that opposition to the death penalty is gaining momentum at this time, a trend which E.J. Dionne Jr. has written more positively about recently also in the Washington Post. A similarly more favorable take on the abolition of capital punishment was offered to members of the Sant-Egidio Community by Pope Benedict XVI in November 2011: “I express my hope that your deliberations will encourage the political and legislative initiatives being promoted in a growing number of countries to eliminate the death penalty and to continue the substantive progress made in conforming penal law both to the human dignity of prisoners and the effective maintenance of public order.”

Of course, much of this rethinking of the death penalty is due to growing concerns about (not in any particular order): 1) possible mistakes that may lead to wrongful convictions and the executions of possibly innocent persons; 2) possible unfairness in its application (do race or economics bias the process?); 3) questions concerning whether or not it is an effective deterrent to violent crime (obviously, it doesn’t deter persons like Breivik or Timothy McVeigh or the 9/11 terrorists who are willing to die); and 4) the apparent high costs for states (and therefore for taxpayers) to implement it. Lane writes, “Such practical and moral concerns are at their most understandable in run-of-the-mill convenience-store murder cases, where the risk of error seems relatively high compared with the benefits of punishing murder with death.” However, Lane adds, “But Breivik’s was no ordinary crime. It presents the special case of a cold-blooded massacre of children by a political terrorist whose guilt is unquestionable and who remains utterly unrepentant; indeed, he told the court that he would kill again if given the opportunity.” While Lane expresses some worries that a sentence of life in prison may dangerously allow Breivik to “broadcast his message to receptive audiences” or perhaps even to escape (and, I might add, he may pose a deadly threat in prison to fellow inmates and detention officers), his greatest concern is a moral one.

That is, Lane submits that “one of humanity’s oldest and most persistent moral intuitions [is] that there should be condign retribution for the most monstrous transgressions.” He then provides a link to a statement made by Thomas Indrebo in the immediate aftermath of the bloody rampage: “The death penalty is the only just sentence in this case!!!!!!!!” To be sure, I suspect this indeed is what many, perhaps most, people feel in cases involving crimes of this magnitude. As a former law enforcement officer who worked in a maximum security jail, I sometimes stood face-to-face with murderers, who though not in the same league as Breivik would not, I knew, hesitate to kill me. Society should be protected from such persons, and this is of course one of the responsibilities of government.

Still, even if Lane is right about the moral intuition that most people have about condign retribution for atrocities that persons like Breivik have committed, apparently not everyone has it or at least stays on that level. A significant voice in support of the ban against the death penalty in Connecticut was that of families of murder victims there. There are other similar persons in groups like Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation. Marietta Jaeger, for example, whose seven-year-old daughter, Susie, was kidnapped and murdered during a camping trip in 1973, says in an article in Sojourners magazine (free registration required) that “there are no amount of retaliatory acts that will compensate for the loss of my little girl or restore her to my arms. Even to say that the death of one malfunctioning person is going to be a just retribution is an insult to her immeasurable worth to me.” More recently, in connection with “A Horrific Crime” committed in Connecticut in July 2007 by two men who invaded the Petit family home and brutally murdered a mother and two daughters, Notre Dame law professor and moral theologian Cathleen Kaveny questions whether “a quick, painless execution” actually serves retribution.

In my view, the Catholic Church today has a principled moral stance that no longer accepts the death penalty as a form of retributive punishment. The current official position of the Catholic Church is offered in the Catechism in its section on the fifth commandment, “You shall not kill,” and in the subsection on “legitimate defense” (I provide the full subsection for context, but punishment and the death penalty are addressed directly in paragraphs 2266-2267):

Legitimate defense

2263 The legitimate defense of persons and societies is not an exception to the prohibition against the murder of the innocent that constitutes intentional killing. “The act of self-defense can have a double effect: the preservation of one’s own life; and the killing of the aggressor. . . . The one is intended, the other is not.”

2264 Love toward oneself remains a fundamental principle of morality. Therefore it is legitimate to insist on respect for one’s own right to life. Someone who defends his life is not guilty of murder even if he is forced to deal his aggressor a lethal blow:

‘If a man in self-defense uses more than necessary violence, it will be unlawful: whereas if he repels force with moderation, his defense will be lawful. . . . Nor is it necessary for salvation that a man omit the act of moderate self-defense to avoid killing the other man, since one is bound to take more care of one’s own life than of another’s.’

2265 Legitimate defense can be not only a right but a grave duty for one who is responsible for the lives of others. The defense of the common good requires that an unjust aggressor be rendered unable to cause harm. For this reason, those who legitimately hold authority also have the right to use arms to repel aggressors against the civil community entrusted to their responsibility.

2266 The efforts of the state to curb the spread of behavior harmful to people’s rights and to the basic rules of civil society correspond to the requirement of safeguarding the common good. Legitimate public authority has the right and duty to inflict punishment proportionate to the gravity of the offense. Punishment has the primary aim of redressing the disorder introduced by the offense. When it is willingly accepted by the guilty party, it assumes the value of expiation. Punishment then, in addition to defending public order and protecting people’s safety, has a medicinal purpose: as far as possible, it must contribute to the correction of the guilty party.

2267 Assuming that the guilty party’s identity and responsibility have been fully determined, the traditional teaching of the Church does not exclude recourse to the death penalty, if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.

If, however, non-lethal means are sufficient to defend and protect people’s safety from the aggressor, authority will limit itself to such means, as these are more in keeping with the concrete conditions of the common good and more in conformity to the dignity of the human person.

Today, in fact, as a consequence of the possibilities which the state has for effectively preventing crime, by rendering one who has committed an offense incapable of doing harm – without definitely taking away from him the possibility of redeeming himself – the cases in which the execution of the offender is an absolute necessity “are very rare, if not practically nonexistent” (John Paul II, Evangelium Vitae).

As the Catechism acknowledges, the state has the authority and the responsibility to inflict upon criminals a “punishment proportionate to the gravity of the offense” in order to redress “the disorder introduced by the offense.” This is punishment that satisfies retributive justice. In addition, when an offender owns up to their crime and accepts the fitting punishment, it becomes expiatory and thereby medicinally puts the prisoner on the path to correction (hence one of the better names for what I used to do is “corrections officer’–and, believe me, I was called a lot worse…). This appears to be a nod in the direction of punishment that is congruent with restorative justice.

However, and very significantly, the Catechism no longer includes mention of capital punishment in paragraph 2266. It used to, though, in the 1992 version of the Catechism, paragraph 2266, which read: “Preserving the common good of society requires rendering the aggressor unable to inflict harm. For this reason the traditional teaching of the Church has acknowledged as well-founded the right and duty of legitimate public authority to punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime, not excluding, in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty.” The line in bold here was omitted, however, when it was revised in 1997 (partly due to the influence of Sister Helen Prejean whose letter about precisely this was delivered to Pope John Paul II on January 22, 1997, seven days before Cardinal Ratzinger announced that a change would be made in the Catechism to reflect recent “progress in doctrine” about the death penalty; see her account of this in her book, The Death of Innocents: An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions [Random House, 2005], 128-132, where she also writes that the “omission changes everything,” 130).

Accordingly, the death penalty is explicitly mentioned in the 1997 version of the Catechism in paragraph 2267, where an execution is justified “if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.” In other words, the only justification for killing a prisoner (as long as it is certain that he or she is truly guilty and no mistake has been made) is if there is really no other way to protect others–conditions that the Catechism, echoing Pope John Paul II, says are just about practically nonexistent today.

In a careful and detailed study of this subsection of the Catechism, E. Christian Brugger comments, “The principal theoretical implication of the shift for Catholic moral teaching is that the death penalty precisely as punishment is no longer being defended, but rather the death penalty as collective self defense” (“Rejecting the Death Penalty: Continuity and Change in the Tradition,” Heythrop Journal [2008], 388-404, at 388). Brugger argues that this current teaching “against capital punishment derives in the first place from the inherent dignity of the human person” (397) as made in “God’s image” (Gen. 1:26-27) and which is “inviolable”–a term that he notes John Paul II used often throughout his writings, including Evangelium Vitae (398). Brugger hastens to add (I think rightly):

This is not to say that the intentional killing of a murderer by public authority is as gravely wrong as the intentional killing of the innocent…. Most people feel much greater emotional repugnance at the thought of killing the innocent than they do at killing the guilty. This is because the two kinds of killing are different in a very significant respect. It does not follow, however, that the one is wrong and the other legitimate. Both are seriously wrong, though one is more gravely wrong than the other” (399).

I agree that the Catholic Church’s teaching on the death penalty is now a principled, moral-theological stance, and I would add another possible reason for the change that was made in the Catechism. Some fairly recent remarks by Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, who is the Preacher to the Papal Household (under both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI), in some of his Lenten homilies in 2004 and 2005, corroborate my interpretation–especially about how the death penalty should no longer serve retributive punishment. In his third Lenten sermon from 2005, Fr. Cantalamessa (explicitly drawing on the work of literary-critic turned anthropologist René Girard) preached that:

Jesus unmasks and tears apart the mechanism of the scapegoat that canonizes violence, making himself innocent, the victim of all violence…. Christ defeated violence, not by opposing it with greater violence, but suffering it and laying bare its injustice and uselessness…. ‘One died for all.’ The believer has another reason–Eucharistic–to oppose the death penalty. How can Christians, in certain countries, approve and rejoice over the news that a criminal has been condemned to death, when we read in the Bible: ‘Do I indeed derive any pleasure from the death of the wicked? says the Lord God. Do I not rather rejoice when he turns from his evil way that he may live?’ (Ezekiel 18:23).”

What Fr. Cantalamessa is getting at is that in the Eucharist we Christians encounter (and hopefully in turn embody) a justice that turns our standard, retributive notion of justice on its head. At the same time, the expiatory sacrifice of Jesus Christ, wherein he nonviolently accepted and died a cruel death and, in doing so, exposed the myth of redemptive violence that hides behind the curtain of state-sanctioned executions done in the name of retributive justice.

On the first point, in Responses to 101 Questions on the Mass (Paulist Press, 1999), Kevin W. Irwin similarly holds that the Mass offers an experience and understanding of justice that runs counter to the retributive moral intuitions of most people:

It is this kind of justice [the justice of the Eucharist] that should be the measure of the world’s and the church’s expectations, but so often it is not. All too often, we fall back into something akin to what is really condemned in the gospels—an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth—whereas God’s justice measures out mercy, not condemnation; grace, not judgment. So, in this sense, it is most helpful that justice and liturgy have been reunited. Hopefully, this will mean that God’s often confounding, always liberating power will break through these rites and ceremonies so that what we experience is an ever more complete identification with God through Christ” (180).

On the second point, in The Executed God: The Way of the Cross in Lockdown America (Fortress Press, 2001), Mark Lewis Taylor similarly writes:

The state, with its dramatic and awe-inspiring spectacles of execution, with its carefully orchestrated ritualized killings, takes on a kind of religious function. This is not just because it exercises an ultimate power over life and death, but because it uses and constructs rituals out of this process of killing and dying. The practice and protocol of execution, we might say, is a kind of human sacrifice, like that maintained in religio-imperial systems of the past” (41).

Finally, one of my teachers, the late Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder, wrote that Jesus’ execution on a cross “puts an end to the entire expiatory system, whether it be enforced by priests in Jerusalem or by executioners anywhere else” (H. Wayne House and John Howard Yoder, The Death Penalty Debate: Two Opposing Views of Capital Punishment [Word Publishing, 1991], 128). One of Yoder’s teachers, Karl Barth, put the matter this way: “Now that Jesus Christ has been nailed to the cross for the sins of the world, how can we still use the thought of expiation to establish the death penalty?” (Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/4, pp. 42f) How are we to understand what they are claiming about Jesus’ crucifixion?

First, I do not think that taking Jesus’ execution as our theological point of departure necessarily entails embracing a traditional satisfaction theory of atonement that might contribute to ongoing support by Christians of the death penalty. Taylor suggests that “Christian scapegoating interpretations of Jesus’ death bear a significant responsibility for today’s theatrics of terror, as we suffer it in the form of prisons, endemic police brutality, and state-sanctioned executions” (108). Sister Helen rightly calls this theology, which she thinks Christians over the centuries have espoused, into question, “Is God vengeful, demanding a death for a death? Or is God compassionate, luring souls into love so great that no one can be considered ‘enemy’?” (120)

Second, Yoder argued that the execution of murderers (and those guilty of any of the other twenty-some capital offenses mentioned in the Hebrew Scriptures) was a form of sacrificial expiation to placate a God who they believed required such practices for atonement. Indeed, according to Dennis Gaertner, in the Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, execution by stoning in the Hebrew Scriptures was “an action conveying a corporate obligation for removing sin from the community” (1253). Glen H. Stassen and Michael L. Westmoreland White make a similar point in their careful study of “Biblical Perspectives on the Death Penalty” (in Religion and the Death Penalty: A Call For Reckoning, eds. Erik C. Owens et al. [Eerdmans, 2004]): “Various crimes in ancient Israel were viewed as so grave that they polluted the people and required some form of ritual cleansing or expiation in order to restore the people’s holiness” (125). They offer several examples where offenders “profaned” themselves and the community, so that the evil needed to be “purged” (note the language). In other words, a serious offense committed by one person could result in God’s punishment upon the entire community; therefore, if known, the perpetrator was executed. Similarly, and focusing specifically on the offense of murder, according to Paul D. Simmons, in the Mercer Dictionary of the Bible, “Killing the murderer was not so much retaliation, punishment or vengeance, as an expression of the belief that innocent blood polluted the land, which belonged to Yahweh (Num 35:33)” (858). I suspect that Fr. Cantalamessa probably had something like all of this in mind when he preached what he did above, and I also wouldn’t be surprised if such theological thinking contributed to the change that was made in the Catechism.

Therefore, if we Catholics believe it is the case that Jesus’ death has done away with the sacrificial system, and if part of that edifice was capital punishment, then just as we no longer practice animal and grain sacrifices to placate God, so too we ought not to perform human sacrifice by executing criminals to satisfy some retributive notion of justice being served. Accordingly, from the Catholic perspective at this time, executions by the state are justified, if at all, only to protect society, but never as a condign retribution or capital punishment.

There are two problems with this analysis. First, if it is correct then it is not merely a development of doctrine but a repudiation of it as it existed for 2000 years. I am unwilling to accept that the Early Fathers and Doctors of the Church, a half dozen earlier popes (going back 1600 years), and all the prior catechisms had it wrong.

Second, if you argue that retribution does not justify capital punishment, how is it possible to argue that protection justifies it? You’ve already recognized that retributive justice is the primary objective of punishment (CCC 2266), so if the primary objective does not justify something how can it be justified by a secondary objective?

I understand the desire of those who oppose capital punishment to find a theological argument to support that position … but they haven’t found one yet.

Ender: I’m still working my way through the literature from the tradition. My work is in progress. For now, the article I cited by Brugger (with whom I do not usually agree on many other things) goes into the writings of the early Fathers, the Doctors of the Church, and the Popes–and Brugger finds a surprising lack of mention of retributive justice in connection with the death penalty. So, for now, I just mention that to say that I’m not sure at this point whether your assertion is true. As for catechisms, Brugger (I don’t have that article at home in front of me right now) shows that those that bring up retributive justice are fairly recent historically speaking and go back only a few hundred years.

Second, retributive justice is the primary objective indeed of punishment according to the current Catechism, but executions (addressed in the later paragraph) are not considered a form of punishment. The catechism does not refer to protection as a “secondary objective” of either punishment or of executions. Indeed, this whole section of the Catechism is primarily about “legitimate defense” and executions are, I think, directed toward that objective.

As for your final allegation, as a former law enforcement officer, I actually used to support capital punishment. However, through my experience in that field–and having personally known a number of both murder victims and persons accused of murder–and subsequently through my theological training and ongoing research, I have over the years come, yes, to oppose capital punishment. But I certainly cannot be accused of letting the tail (opposition to capital punishment) wag the dog (of my reading of theology).

Dr. Winright: Thank you for your considered remarks. Regarding the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, according to Cardinal Dulles they: “are virtually unanimous in their support for capital punishment.” As for the concept of retributive justice in connection with capital punishment that is rather fully laid out in the Catechism of Trent, and the five catechisms (of which I am aware) preceding the current 1997 version all said essentially the same thing: the State has “the right and duty … to punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime not excluding, in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty.” (1992 edition).

As for executions not being a form of punishment, I find this claim baffling. I recognize how one could reach this conclusion from reading CCC 2266-2267, but surely if a conclusion conflicts with reality it ought to be rejected. Capital punishment of course is punishment. It has been considered that since the beginning of history. If you called a tail a leg would a dog have five legs? Obviously not: changing the name of something doesn’t change its nature (Lincoln). Capital punishment is the most serious form of punishment and arguing that point seems a bit like arguing that circles aren’t round.

As for protection being a secondary objective, if an action has multiple objectives and one is primary then by definition all others are secondary. We know that retribution is the primary objective of punishment therefore rehabilitation, deterrence, and protection are all secondary.

I meant no offense by my final comment before. Each of us would like to believe that our positions are fundamentally sound and accord with Church teaching but while I have read a number of opinions opposed to capital punishment I have yet to find one that seems defensible based on what the Church has taught. I find CCC 2267 at odds with the entire body of Church teaching and see no way to reconcile it (other than as a prudential recommendation rather than a new doctrine).

Ender: Thanks for the follow-up. For now I can reply by drawing on the aforementioned article by Brugger. I have read all that Dulles wrote on the subject, and in my judgment his treatment of the topic pales in comparison to the detailed research of Brugger. Indeed, this topic was not one of Dulles’ areas of expertise. According to Brugger, “In theology we need to wait 300 years after Aquinas to find explicitly retributive justifications for inflicting the death penalty. Historically speaking, systematic arguments from retributive premises are relatively new” (393). The Roman Catechism of 1566 refers to retribution in a “subtle” way (389), and the 1598 Catechism of Robert Bellarmine is more explicit and strong about retribution. Earlier, Clement of Alexandria taught that the primary purpose of punishment was medicinal and secondarily it was meant to protect the health of the body/community. Origen also argued that the death penalty was to protect the community and also to deter. Augustine emphasized its deterrent effect, but he also implored a judge to spare the lives of two condemned men. He went on to write that “extreme necessity” might require the death pf criminals, but only if they prove to be incorrigible (I’m drawing from Brugger 390 and 394 so far). Indeed, Augustine’s mentor, Ambrose, wrote one of the strongest treatises against capital punishment in the entire tradition of the Church.

Returning to Aquinas, Brugger writes, “It is interesting to note that although Aquinas has a very carefully formulated account of the retributive purpose of punishment generally, he does not appeal to retributive reasoning when arguing for the legitimacy of making punishment capital. He refers rather to reasoning drawn from his part-to-whole analogy. In this way, his accounts justify capital punishment, not specifically as means of redressing criminal guilt and the disorder introduced by the criminal’s crime, but because the ‘health’ of the community demands it” (392-3).

I’ve read Brugger’s other article on this matter in The Thomist, where he critiques (persuasively, in my view) a counter-interpretation of Aquinas on this matter by Steven Long in The Thomist. In addition, there is Brugger’s lengthy book on the subject (and another one by James Megivern), and I have yet to read a book-length theological account that persuasively argues otherwise. Until one comes out, I find the scholarship of Brugger (and Megivern) more persuasive (which doesn’t mean I agree with everything they’ve written).

Your other comments here, I think, are begging the question.

Finally, there is no reference to prudence in this section of the Catechism, but here’s how I would see it in this connection: Prudential judgment would come into play ONLY with regard to the question of whether a) a particular state is truly able to protect its citizens from a threatening prisoner through means other than execution; or, put differently, b) whether a particular threatening prisoner in certain circumstances poses a grave and imminent threat to society. These are prudential judgments, for prudential judgment has to do with the APPLICATION of the Church’s teaching to a particular, concrete case. There is no prudential judgment to be made about the Church’s teaching and whether or not one agrees with it.

The Church’s teaching has changed and/or developed before on other matters (including religious liberty, which many US bishops now applaud and defend vociferously even though it was condemned on the Syllabus of Errors a century-and-a-half ago). In my view, the Church’s teaching on executions by the state has similarly changed and developed. And, as I attempted to argue in my original post, there are solid biblical and theological reasons for this that are now coming to light more. Indeed, Dulles once argued that the liturgy is a significant thread in the Church’s tradition, so perhaps in a way what the preacher for the papal household is suggesting (about the Eucharist in this connection) is also very traditional (even if it wasn’t always understood in this connection).

Regardless of what other arguments were made earlier, what we see in the current catechism is that retribution is the primary objective of punishment. This makes protection, deterrence, and rehabilitation all secondary objectives so the question remains unanswered: if the primary objective does not justify the punishment how is it that a secondary objective can justify it?

I agree with your comments on prudential judgment but, whether the catechism mentions it or not, quite clearly your comments apply to the third part of CCC 2267. Any evaluation of the capabilities of modern penal systems (and specifically that they have the means of “effectively repressing crime”) is undeniably prudential. Looking at the other two statements in that section it is clear that the first one is simply incorrect: the Church never had the restriction on the use of capital punishment it claims.

If Brugger’s position that 2267 represents a new doctrine it is not mere development, it is rather the repudiation of a doctrine that stood unchanged for (at least) 1600 years. I don’t have access to Brugger’s book and have not seen his article in The Thomist (I’ll certainly look for it) but if his position is to stand it has to address not merely what Aquinas said (or didn’t say); it has to address Gen 9:5-6. This is the passage the Church cites – specifically in the Catechism of Trent – and forms the basis for Church teaching on the subject. Those passages are cited in CCC 2260 with the helpful explanation that “This teaching remains necessary for all time.” Are we to understand that “for all time” means only “until you reach 2267”?

And this goes to the second claim in 2267 that imprisonment rather than execution is “more in conformity with the dignity of the human person”; on what is this based? This assertion seems to be the heart of the issue but how are we to understand the validity of the claim based on Church teaching? The passages in Genesis state that it is because of the dignity of the victim – because he was made in the image of God – that the life of the murderer is forfeit. The new position turns that assertion on its head and holds that because of his dignity the life of the murderer is protected.

As I said before, the most rational way to reconcile all of this is the way Dulles did, that JPII believed capital punishment caused more problems than it solved and that – for entirely prudential reasons – it should not be used.