Nehemiah 8:2-4, 5-6, 8-10

Psalm 19

I Corinthians 12:12-30

Luke 1:1-4; 4:14-21

Words are amazing things. There is something sacramental about them, in so far as they can, in a sense, make something “present” merely by signifying it. And excepting onomatopoeic words, the means of this signification need not bear any intrinsic relation to what is signified. There is nothing about the utterance of the words “freshly baked brownies,” for example, that suggests that they refer to a chewy chocolate dessert. Yet these mere words have to power to evoke (and rather vividly) a very specific smell in the mind of the one who understands the reference. “How is it,” I ask my students, when I perform this thought experiment in class, “that you can almost literally smell fresh brownies right now, even though there are none anywhere near here? I’m able to make them present to you, even if only in your mind, simply by making certain sounds with my mouth.” It is such an obvious thing, and yet if we take the time to dwell on it, also very mysterious.

Things get even more mysterious when we consider how this act of signification can make things present across chasms in time. It can be disquieting to wonder about how many significant human events and even entire cultures have been consigned to oblivion because of the fact that nobody could write things down, or because the written records had been lost. Indeed, it is a kind of miracle that events from thousands of years ago, together with all the human drama that accompanied them, can still be made present to us today through the power of language. Words are amazing things; powerful things!

We see the power of this everyday miracle on full display in the first reading for this Sunday, from the book of the prophet Ezra. “Ezra the priest brought the law before the assembly,” a gathering of the people who had all but forgotten the history and practices that made them who they were. Just as each year the Hagaddah transports the people of Israel to the night before their departure from Egypt, so the reading of the Torah transported the people gathered around Ezra to the base of the holy mountain. Once again God was uttering his Law to his people, telling them in meticulous detail how they are to act and live together, that they might be fully present to one other, and that God himself might come and live in their midst.

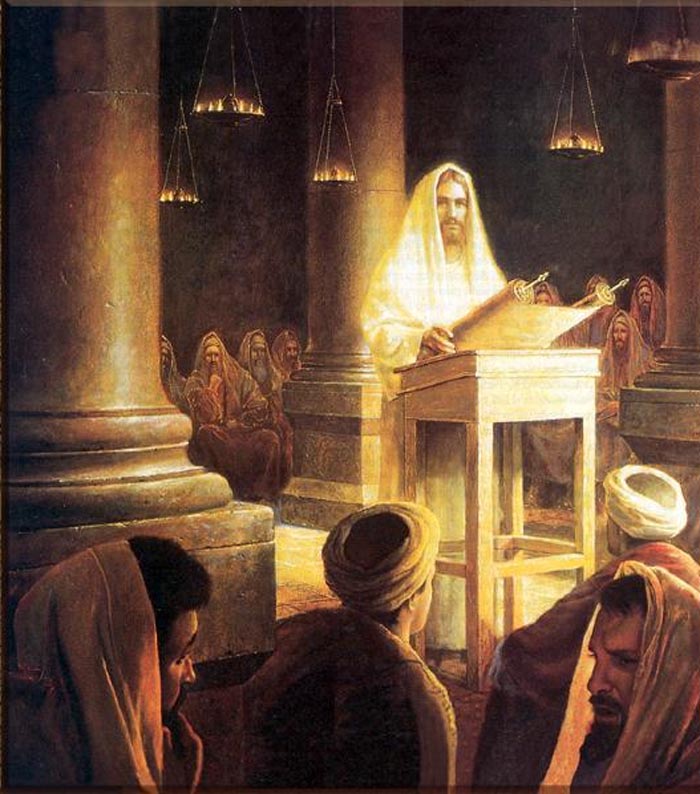

The reading of the Law was a big deal. They built a raised platform from which Ezra was to read. Everyone—even the children—stood “from daybreak till midday” (with no cry room, presumably) listening to the words of the Lord, as well as Ezra’s explanation of their meaning. Yet as they heard the words pour forth, their anticipation somehow turned to fear and sadness. They affirmed what was being proclaimed, shouting “Amen! Amen!” but then they “bowed down and prostrated themselves before the LORD, their faces to the ground.”

They were struck down; the great gift, once uttered, had become a curse. For when the Lord returned through these words, spanning the centuries since Israel’s liberation, the people recognized that their lives did not match what the Lord expected to find there. There must have been a kind of nostalgia at work there; certainly not the sentimental kind that accompanies a “stroll down Memory Lane”, but rather the piercing kind that marks the memory of a mission or an identity lost, a true love unknowingly forsaken, a true home thoughtlessly abandoned. Perhaps it may have been similar to the nostalgia felt by the Prodigal, remembering his father as he fed the pigs. Nonetheless, it pierced them to the heart, and filled them with the sorrow of one looking in from the outside.

The question is whether the message God is conveying to the people—the word by which his will becomes present to them again—is good news or not. For the people, it was not, because all they saw was the distance between who they were and who God called them to be. But what Nehemiah and Ezra saw was something different: the assurance that God had not abandoned his people, and thus the hope that the promises which made the people who they were would yet be fulfilled. “Go, eat rich foods and drink sweet drinks,” they told them, “and allot portions to those who had nothing prepared; for today is holy to our LORD.”

When a person places themself before God, their primary object of attention must be either themselves or God. The gravity of one’s focus must be centered upon one subject or the other. Everything rests upon this difference, it seems: to encounter God with an eye toward its implications for oneself could only engender fear and sadness. Such was the attitude of the assembly, since for them, the primary meaning of the Law’s revelation was their own inadequacy. One cannot help but think here of the rich young ruler who, though better than most, ultimately balked at Jesus’ invitation to complete divestment, and so “went away sad.”

But to encounter God with an openness to being captivated entirely by his goodness and fidelity (hesed) is to discover a profound and unconditional joy. “Do not be saddened this day,” say the prophets to the people “for rejoicing in the LORD must be your strength!” Yes indeed. To rejoice in who God is: that is the path to true courage and happiness. It is ultimately all about God in the end.

Which brings us (finally) to today’s gospel reading, the punchline of which is delivered by Jesus himself: “Today this Scripture passage is fulfilled in your hearing.” For the longest time, I passed over this line as simply another occasion in which Jesus declares himself to be the long-awaited Messiah, the one foretold by the prophets, the “one who is to come.” But surely there is more to it than that, since Jesus’ claim is aimed directly and primarily at the Scripture passage, and its relation to the present moment. It is therefore only indirectly and secondarily about his own identity. So what could it possibly mean for a Scripture passage to be “fulfilled in one’s hearing”? Here is the passage he read in the synagogue that day:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring glad tidings to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to proclaim a year acceptable to the Lord.

Its fulfillment, then, necessarily has both a past and future dimension. The first part, related to the past, is about speaker’s claim to be anointed for a particular purpose, and filled with the Spirit of the Lord in order to carry it out. The second part, then, elaborates upon this purpose and points to its future consequences: liberation, healing, justice and peace. For it to be “fulfilled in our hearing,” then, couldn’t it mean that it is simply true, and that it mediates the Lord’s presence to the people through his saving promises? Perhaps, but Jesus of course intends more than that.

The power of words to make present what they signify is now surpassed by another, far greater power of mediation: the person of Jesus Christ, who is the Lord incarnate, the very Word (logos) of God. Ezra turned the people’s self-involved anxiety into gladness by turning the people’s attention toward God’s goodness and faithfulness. Jesus, likewise, invites those who heard him in the synagogue that day to go beyond their usual textual and theological analysis—their never-ending attempt to “get it right”—and to open themselves up the loss of the very text itself as a self-standing and self-sufficient medium.

It is as if Jesus is saying to this assembly (to risk a speculative elaboration) : “I am the one you’ve been waiting for. It’s me. I’m here. Forget for just a moment what my interpretation of this passage might mean for you and your comfort zone. I am the Word in which all words inhere. This prophecy is true because I am uttering it to you right now. Isaiah spoke it to you only because I am speaking it to you right now. I am the one who is going to give it to you. You can stop trying to figure it all out now. You won’t be able to save yourself. I am the living Torah. I have come among you, that you might the liberation, healing and life that you have sought for so long. I will give you my body, and you will be my body in the world. You have these scrolls for now, but I am the only one able to break the seal of the scroll that will give you life eternal, for I am the Lamb, the faithful witness, who is broken for you.”