Isaiah 5:1-7

Psalm 80:9, 12, 13-14, 15-16, 19-20

Philippians 4:6-9

Matthew 21:33-43

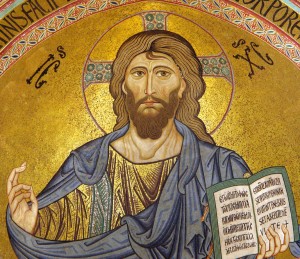

“Pammakaristos Church – main dome of parekklesion – Jesus Christ – P1030432” by User:Vmenkov – Own work.

I have never preached but I imagine this week’s gospel reading is one that make homilists sigh. I know I did as I read over the readings for this week, tempted to ignore it in order to focus on the second reading, which really is lovely and so much easier to reflect on from the perspective of moral theology.

The gospel passage for this Sunday is the parable of the vineyard. It is heavily allegorical. The vineyard is Israel. The tenants are the leaders of Israel. The landowner is God. The servants are the prophets. The son, obviously, is Jesus. The theological thrust of the package concerns the suffering and persecution of God’s prophets and puts Jesus in continuity with those who came before him. But in Matthew’s version of this parable that we read this week (it is also in Mark), Jesus concludes

“Therefore, I say to you,

the kingdom of God will be taken away from you

and given to a people that will produce its fruit.”

It is a problematic passage. While it is clear that Jesus is addressing the leaders of Israel, as Ulrich Luz notes, “the idea of the entire nation of Israel is not far removed.” Luz continues,

As early as the Deuteronomistic tradition of the murders of the prophets it is always Israel as a whole that has rejected and killed the prophets who were sent. . . Above all, however, [the readers] will note that the text replaces the Jewish leaders not with different, better leaders but with a ‘nation.’ . . Does that not mean, therefore, that the issue is not only Israel’s leaders but the entire nation?”

Dan Harrington too references this interpretation: “The parable of the vineyard (and especially its Matthean applications in 21:41, 43) is often taken as evidence for Christian replacement or supersession of Israel as the people of God.”

There are some ways around a supersessionist reading. Harrington, for example, emphasizes the context of the conflict with Israel’s leaders in his argument over how to interpret the passage, emphasizing that supersessionist claims are to be avoided by reading the “nation” as a “‘group of people,’ in this case the leaders of the Jewish Christian community.” We might also ignore supersessionist implications and any questions concerning who Matthew thought was in and out of the kingdom and turn the passage back on ourselves as the church. Are we also rejecting the stone that has become the cornerstone? Does the church bear guilt today of persecuting God’s prophets. In such a way, the moral implications of the text might still bear weight apart from questions of Israel at all.

Luz, on the other hand, claims that we cannot simply dismiss the problematic nature of the text by claiming that Jesus was only thinking of the Jewish leaders. He writes that “Instead, we must take the text seriously just as it appears in the Bible. We must accept it along with what has resulted in our history from the disinheriting of Israel, for which it is partly responsible. One does not undo guilt by repressing it.”

Such problematic passages are so important in the lectionary because they remind us that as Catholics, we are not just “people of the book.” While Scripture is integral, foundational, and indispensable in the life of the Church, we must be reminded that we do not simply move seamlessly between the text, its context, and its implications (whether ecclesiologial, soteriological, or moral) for us today. The text and its context speak in conversation with other authorities, including the experience of the Church (in this case, with anti-Jewish readings that act as their own stumbling block to recognizing that Jews and Christians worship the same God) to continuously reinterpret the text. Sound exegesis is not enough for God’s word to speak. Instead, the living experience of the Church must bring the text to life, and readers must trust the Holy Spirit to speak through the text in ways that the author might not have imagined.

Yes, this is a passgae which makes homilists sigh, and one which I’ve been sighing over this week ! Thanks for a helpful post.

A homily might focus on “living with our failures” and could link in well to the current synod on the family, both in terms of the Church’s failure to be sufficiently pastoral, merciful and forgiving and hence people going else where / lack of fruit; and coping with marriage/family failures.

Much of this passage is Matthew and not Jesus, writing for a Church community increasingly estranged from Judaism.

The Church has much to learn from the subsequent development of rabbinic Judaisim; Vatican II has allowed us to see that rabbinic Judaism has indeed produced much fruit, and fruit which the Church still has much to learn from.

God Bless

Getting the exegesis right is important, but also the ecclesial context as well as an analysis of the assembly are crucial. When I imagine my Chilean parish for this weekend, I call to heart and mind the invitation by Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium to be “missionary disciples” and the struggles to move out from ourselves as the Holy Father and the Gospel call us. This parable also can ask us to examine in what way we serve as workers in this vineyard. Do we recognize God as the owner of our lives and all that we own and have? Do we give to God from the “first Fruits” (themes of stewardship and tithing emerge naturally).