To many of our readers, I realize I may appear to be obsessed with subsidiarity and food stamps (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program/SNAP). In the last year, I have written about a dozen blogs focused on poverty, with many of them highlighting SNAP in some way. Why SNAP? Because it is a program that has been demonstrated to work – it is a means tested, effective program that accomplishes BOTH feeding the hungry and stimulating the economy.[1] Without repeating what I said in Subsidiarity is a Two-Sided Coin and Missing the Point on Poverty, once again I must draw attention to SNAP and the dangerous nature of proposals to cut SNAP being debated in Congress right now. It is my contention that turning SNAP into block grants to the states would violate the basic principle of subsidiarity, as maintained in Catholic social teaching.[2]

In the wake of the financial crisis and recession, we have learned that elements of our safety net work quite well. In his testimony before the House Budget Committee, Robert Greenstein (President of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and former Administrator of the Food and Nutrition Service at USDA),

the poverty rate stood at 15.5 percent in 2010. Yet under the same measure, the poverty rate without the safety net — that is, the poverty rate based on household incomes before government assistance is counted — was 29 percent. In other words, the safety net cut poverty nearly in half compared to what it otherwise would be.

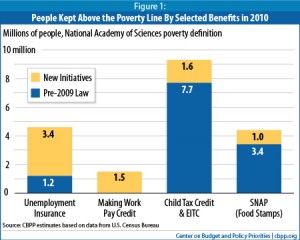

Looking at the hard data, 4.4 million people were kept out of poverty in 2010 through both the existing law and new expansions and initiatives. Increases in the cost of SNAP is due to three things: the increase in benefits (set to expire in November 2013), increased participation of eligible persons/families, and the increase in eligible persons due to the recession/ unemployment. Some of these increases will automatically go down as the economy recovers and unemployment falls; however, increased benefits and participation by eligible families should be maintained. (I am emphatically stating greater participation by eligible families is a desired goal. SNAP’s success in providing nutritional assistance to low income persons requires participation by those in need).

What is heartening in this data is that key elements of the safety net worked as they were intended. As unemployment rose, the poverty rate went up only marginally. Why? Because SNAP has “automatic stabilizers” built into the structure of the program. In times of economic hardship, the cost of SNAP automatically increases (the costs entirely covered by the Federal government) while it decreases in times of high employment. This responsiveness in SNAP is crucial and we must maintain this structural integrity. If SNAP is converted to block grants, then the federal government will simply give set money to the states and they will have to stay within that amount (or make up the difference from already strapped state budgets). If converted to block grants, Robert Greenstein explains:

What is heartening in this data is that key elements of the safety net worked as they were intended. As unemployment rose, the poverty rate went up only marginally. Why? Because SNAP has “automatic stabilizers” built into the structure of the program. In times of economic hardship, the cost of SNAP automatically increases (the costs entirely covered by the Federal government) while it decreases in times of high employment. This responsiveness in SNAP is crucial and we must maintain this structural integrity. If SNAP is converted to block grants, then the federal government will simply give set money to the states and they will have to stay within that amount (or make up the difference from already strapped state budgets). If converted to block grants, Robert Greenstein explains:

• SNAP would no longer be able to respond to increased need during economic downturns, resulting in increased hardship and hunger in recessions.

• Nor would SNAP be able to bolster the economy during recessions as it does today. In studying the effect of 22 different tax and spending options to promote economic growth and jobs in a weak economy, economist Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics rated temporary increases in SNAP benefits first in effectiveness per dollar of cost, ahead of both unemployment insurance and all tax-cut options. CBO also gives SNAP increases its top rating for effectiveness in a weak economy. This is because SNAP benefits are quickly spent and injected into the economy, rather than saved. Preventing SNAP from expanding automatically as the economy weakens by converting it to a block grant would remove what economists call an “automatic stabilizer” and hence likely make recessions somewhat deeper and longer.

What would have happened to those 4.4 million Americans if SNAP had not had the ability to “auto stabilize”? As that data shows, poverty would have risen significantly between 2008-2011. While the recession is the dominant reference point for the current discussion, the ability of SNAP to respond does not just apply to nation-wide economic turmoil. The structure of SNAP as it exists now allows it to automatically accommodate for natural disaster (like Katrina or a Tornado) or for localized economic change like the closing of a manufacturing plant. State block grants would not be able to do this. Any response to such eventualities would require requesting increased budgets from the Federal government and at best, would significantly delay responses in times of crisis.

The evidence for my claim is found within the 1996 Welfare Reform which created Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) as block grants to the states. The same data which shows the effective responsiveness of SNAP has exposed the limitations of TANF to respond in times of economic hardship. SNAP succeeded in responding to need, TANF was unable to do so, steadily falling in its ability to respond. For the background and data on this, See: “TANF weakening as Safety Net” as well as sections of Greenstein’s testimony cited above.) While I do not wish to debate the ins and outs of welfare reform here, it provides firm evidence that block grants would cost SNAP the ability to “auto stabilize.” This is part of why maintaining the structural integrity of SNAP is, in my opinion, a moral imperative.

What does this have to do with subsidiarity?

Subsidiarity includes within it the responsibility of larger orders in society to step in when lower levels are unwilling or unable. The issue here is not the state’s desire to meet the nutritional needs of its citizens but it ability to so without the federal structure of SNAP. States are not able to simply run deficits; the federal government has the necessary ability to run deficits when required. The federal government is the single entity that can expand spending during an economic contraction, when needs for these programs increases dramatically. Therefore, sending SNAP back to the states should not be the goal, the federal government is the proper level of authority to maintain this effective and necessary element of our safety net.

It is also relevant to my claim concerning subsidiarity, that food stamps was standardized and taken over by the federal government because of the unwillingness and inability of the states to properly and fairly deliver. Greenstein explained to the House Committee:

I am old enough to remember the mid and late 1960s, when each state sets its own food stamp rules, some states cut off families at income levels as low as 50 percent of the poverty line, and some states adopted barriers that impeded participation (in some cases, with disproportionate effects on members of some minority groups). Two teams of medical researchers conducted nutrition surveys in the late 1960s and found rates of childhood malnutrition and related diseases in some poor areas of our country that were akin to those in some third-world countries. This led to a national bipartisan consensus — led by President Richard M. Nixon — to establish national eligibility and benefit standards for food stamps. In the late 1970s, after the national standards had taken effect, the medical teams returned to many of the same poor areas they had studied in the late 1960s and found dramatic improvement among poor families and especially among poor children. Child malnutrition and related conditions had become rare. . . .

The researchers credited food stamps as the single largest factor for this striking progress, concluding that “no program does more to lengthen and strengthen the lives of our people than the food stamp program.” I believe this is a lesson we shouldn’t forget.

Recent history and data concerning the effectiveness of food stamps, as well as the longer history concerning the development of the national standardization are both crucial – both remind us that the goal here is to provide food security to low income persons/families. This is a matter of the common good, of solidarity, and of subsidiarity. Far from being a good application of subsidiarity, proposals to convert SNAP to block grants would represent a violation of subsidiarity.

[2] While I believe a similar and powerful argument can be made for Medicaid block grants, which I also think violate subsidiarity and the common good. The focus of this post is specific – it’s about SNAP. I am not making claims about all block grants or attacking the proper role of states; some things are properly managed through block grants. However, SNAP is not properly managed and situated in the states.

Absolutely agree with you. It is particularly maddening when you learn that the federal government cannot go bankrupt. Our politicians, particularly those most concerned with cutting government budgets, really need a brush up in sectoral balances and basic accounting. Europe is largely rejecting the regimes imposing austerity on them and the crazy thing is that we don’t have to follow that path, because the U.S. is sovereign in its own currency. EU nations must either 1) embrace fiscal unity, 2) adopt austerity and ruin their economies, or 3) abandon the Euro and go back to individual currencies.

The U.S. is threatening to follow the path taken by Greece (#2) when we don’t have to and when it would be insane to do so.

Responsible government budgets are needed, but understanding accounting and currency sovereignty are vital to understanding what ‘responsible’ means for a sovereign government. Cutting programs (or turning them into block grants) like SNAP are in violation of the preferential option for the poor and as you point out in this case, a violation of the principle of subsidiarity.

Sectoral Balances: http://csteconomics.blogspot.com/2012/05/sectoral-balances.html

Responsible gov’t finance: http://csteconomics.blogspot.com/2012/02/functional-finance-govt-household.html

Exactly!

Have you seen: Stiglitz’s new popular piece “After Austerity” – its worth a read.

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/after-austerity