“Embryonic Stem Cell” it seems is the password which justifies just about any laboratory pursuit, no matter how repugnant. Scientists have just created what seems to be the first chimeric monkeys all in the name of advancing our knowledge of how embryonic stem cells function:

“Stem cell therapies hold great promise for replacing damaged nerve cells in those who have been paralyzed due to a spinal cord injury or for example, in replacing dopamine-producing cells in Parkinson’s patients who lose these brain cells resulting in disease,” Mitalipov said in a release from the Oregon National Primate Research Center. “As we move stem cell therapies from the lab to clinics and from the mouse to humans, we need to understand what these cells do and what they can’t do and also how cell function can differ in species.

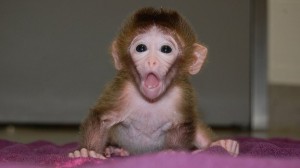

To make the chimera monkeys, scientists used totipotent stem cells (cells which can give rise to a new embryo since they have the ability to differentiate into both placental cells and all animal cells; normally, embryonic stem cell research uses pluripotent cells which can turn into any animal cell but cannot give rise to a new embryo). Researchers combined the totipotent cells of six developing embryos, creating a blastocyst that was larger than normal but still capable of further division and differentiation. They then implanted the mixed embryos into surrogate rhesus monkeys who gave birth to what appear to be three healthy infants, infants who have about six parents. All three are male, though one carries both male and female cells.

Chimeric animals are considered important for researchers who want to figure out how embryonic stem cells turn into working tissues when injected into the body. This research follows closely on the heels of a related landmark in research a few months ago when scientists effectively “cloned” a human being (a process known as “somatic cell nuclear transfer) in order to generate embryonic stem cells for research. The consequent embryos had 69 chromosomes, 23 more than normal and so were useless for research, but scientists hailed the discovery as a monumental stride forward in the effort to create embryonic stem cells which could be used to cure countless human diseases that plague the human race. Once again, cloning, a procedure repugnant to most people when applied to humans, was justified in the name of “embryonic stem cell research.”

Embryonic stem cells have become symbolic of the vast potential of medicine. When we think of embryonic stem cells, we think of people like Christopher Reeve or Michael J. Fox or our neighbor’s child with juvenile diabetes and how all these people could be cured if only we could figure out the secret these cells carry inside them. We are willing to justify virtually any procedure so long as it aims for the end of finding how embryonic stem cells can cure all of all our medical ills. The potential cures offered by embryonic stem cells are the ends that justify any means.

In the process, the line between therapy and reproduction is becoming more and more blurry. In the cloning research, scientists assured naysayers that the embryos they were creating would never become human beings, that is, they would never be implanted inside a woman in order to give rise to a baby. And yet, creating a human embryo for many, including the Catholic Church, is creating a human life, a life which we treat as if it is a person, which should be treated with the same dignity and respect due to any person. And here in the chimera research, we see again how therapeutic research becomes reproductive. Scientists produced new life, new baby monkeys for the sake of therapeutic research. Surely it will be only a matter of time until the same procedure is attempted with human embryos and human chimera babies.

The history of bioethics is riddled with stories of human beings used as a means to a supposed good end: Carrie Buck, the Tuskegee sharecroppers, Mengele’s subjects, the children at Willowbrook, and the list goes on. The new chimera monkeys and the cloned human embryos from a few months ago are just the most recent chapters in the same old story of using the ends to justify the means, a consequentialist mode of moral reasoning which is incredibly prevalent in the field of bioethics. The question I am more interested in is the character question–what does this research reveal about the character of our society? Are we becoming people who are able to see the dignity in all human life, no matter how vulnerable? Are we becoming more patient people in the face of suffering and illness? Are we becoming more just people, who give everyone the care and respect that is due to them rather than unfairly laying excessive burdens on one segment of the population?

Some may argue that our relentless pursuit of cures through embryonic stem cell research is indicative of our compassion for those who are sick and vulnerable. Compassion, however, comes from the Latin words “co-” and “-passio,” that is “suffering with” someone. Compassion is the virtue which allows us, as moral theologian James Keenan says, “to enter into the chaos of another,” to share their burdens, and to suffer with them. Compassion is not just a vague feeling of distress or sympathy for those who are suffering, nor is it a willingness to sacrifice one person for the sake of another. Supporting research like chimeric animals (and eventually humans) or cloned embryos all for the sake of curing disease may feel compassionate, but it is really a way to avoid what compassion actually demands–entering into the chaos of another and being willing to share in another’s suffering even when we cannot fix it.

I think the reason that we are able to justify so many repugnant actions like somatic cell nuclear transfer and chimera techniques in the name of therapeutic advance is because we do not know how to live with illness and suffering. We do not know how to approach the person whose disease has no cure and whose suffering has no solution. In our relentless pursuit for cures, we have forgotten how to care. We place our hope in embryonic stem cell research because it seems to promise us the cure we need to face disease and suffering. In the process, we are bringing forth new life in the laboratory to use for our purposes. In our effort to find cures, we are becoming less able to care.

Now, I am not saying that we should not be trying to cure diseases like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or juvenile diabetes. But the means we choose as a society will largely be determined by our societal character and how able we are (or not) to face illness, suffering, and death with hope and compassion. And our ability to draw the line and declare certain techniques such as this one as immoral will depend largely on whether we are able to imagine some greater evil than suffering and disease, that is, the evil we ourselves do in the name of scientific advancement. I think that creating life in the lab–especially the sort of orphan life that these chimeras are–purely for the sake of research and scientific advancement has clearly crossed that line.