April 10, 2011 Fifth Sunday of Lent

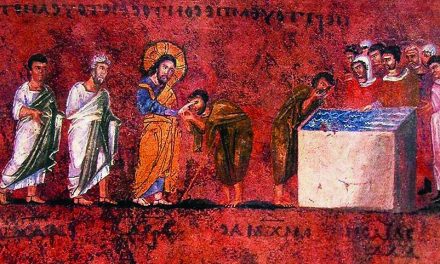

Ezekiel 37:12-14; Psalm 130:1-8; Romans 8:8-11; John 11:1-45

In the Introduction to our book, After the Smoke Clears: The Just War Tradition and Post War Justice, Mark Allman and I start with some words from the prophet Ezekiel. As one of the exiles deported by Nebuchadnezzar in 597 B.C.E., Ezekiel predicted the devastation of Jerusalem. Even if their military defenses were successful in the past, Ezekiel admonished the people about their dangerous illusion of security—promoted by false prophets “saying ‘Peace!’ when there was no peace”—that underpinned their idolatrous way of life marked by vice, unrighteousness, injustice, and oppression. When his dire warning came to pass a decade later, the focus of Ezekiel’s message shifted to the hope of Israel’s restoration, the New Jerusalem. The plain filled with dry bones will be transformed into a habitat full of vitality. The dispossessed would return to their land, rebuild their homes, and regain their livelihoods. God will mercifully redeem them (as the Psalm emphasizes) and will put God’s spirit in the people, so that they might have new life and truly know God in an intimate way that transforms who they are and how they live. This new era was to be characterized by lives devoted to virtue, righteousness, justice, and true peace, or shalom.

Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones scattered across a plain is now, millennia later, frequently seen in news reports on our televisions and computer monitors. The names for these places peppered with bones in our day include but are not limited to Rwanda, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Japan, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Darfur region of Sudan. Many of these are the result of human moral evil; some are from natural disasters. Men, women, children, the elderly—all too many human beings made in God’s image are suffering and dying. They are in need of shalom.

We Christians who believe God has mercifully given us the Spirit and has already raised us to new life—or, as Paul put it, “the Spirit of God dwells in” us and gives “life to [our] mortal bodies also”—are all called to be peacemakers. In their benchmark pastoral letter from 1983, The Challenge of Peace: God’s Promise and Our Response, the U.S. Catholic bishops wrote, “Peacemaking is not an optional commitment. It is a requirement of our faith. We are called to be peacemakers, not by some movement of the moment, but by our Lord Jesus” (par. 333). We should be, like Jesus, “perturbed and deeply troubled” whenever and wherever suffering and death happen. Through God’s Spirit, we should be the face and the hands of God’s mercy and redemption, putting flesh on the bones of this world.