The following is a guest post from Ian Jones, doctoral candidate at Fordham University. His dissertation focuses on the understanding of non-human animals found in the thought of the Fathers–both in the East and in the West. His work has particular relevance as many of us look to situate Pope Francis’ eco-encyclical within the tradition.

One thing we might expect to see in Pope Francis’ ecology encyclical is mention of the often cited concept of human “dominion.” Sometimes we use this term to refer to a divinely granted authority to order the natural world, and if he follows his predecessor, the pope is likely to critique overreaching interpretations of that authority. But Genesis, our source for the term, connects it not to nature generally, but to our relationship to animals specifically.

God grants humans dominion when He creates them in His image and instructs them to “[b]e fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth” (Gen. 1:26-28, NKJV). The Greek word translated “have dominion” is the verb ἄρχω, meaning to rule or govern. Human rule of animals is specially stressed, apart from the broader charge to subdue the earth.

Interestingly, dominion doesn’t include killing animals for food. In the very next verses, God gives both humans and animals a strictly plant-based diet (Gen. 1:29-30). It’s significant that, when God eventually grants Noah and his sons permission to kill animals for food after the Flood, He repeats the commands to “[b]e fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth” (Gen. 9:1), but there’s no mention of the dominion (ἄρχω) that accompanies those commands back in Genesis 1:28. Instead, in connection with this new permission to kill, God speaks of the animals’ fear and dread of humans (Gen. 9:2-3). This is hardly a step up for us. God follows this allowance by forbidding us to “eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood” (Gen. 9:4), reinforcing that life belongs to Him, and that our leave to take it is a special condescension and not a function of our dominion.

What does dominion mean, then? We first see it when God brings the animals and birds to Adam for him to name (Gen. 2:19). Naming indicates not only authority over another but also knowledge of that person or thing, as when Jesus gives Simon the name Peter (Matt. 16:19; John 1:42), or when He tells of the white stone each saint will receive with “a new name written which no one knows except him who receives it” (Rev. 2:17). There’s an element of relationality, then, in the exercise of dominion that is naming.

This “relational” dominion, shown by both Adam and Christ (the New Adam), occurs again and again in the lives of the saints, men and women who are icons of Christ because of the power of His Spirit dwelling in them. They testify to the possibility of a Christ-like way of living, even among the “fallen” conditions persisting in the world. They’re able to regain Eden’s harmony, because they’re transformed by God’s love and, in turn, transform the world around them. So their “environment,” the space around them, becomes more of what it’s meant to be as they become more of who they’re meant to be. In localized reversals of the Fall, the saints’ obedience to the Creator results in the obedience of animals to the saints. The order of paradise is restored, because only when we yield to God’s will do animals yield to ours, human dominion imaging and flowing from divine dominion.

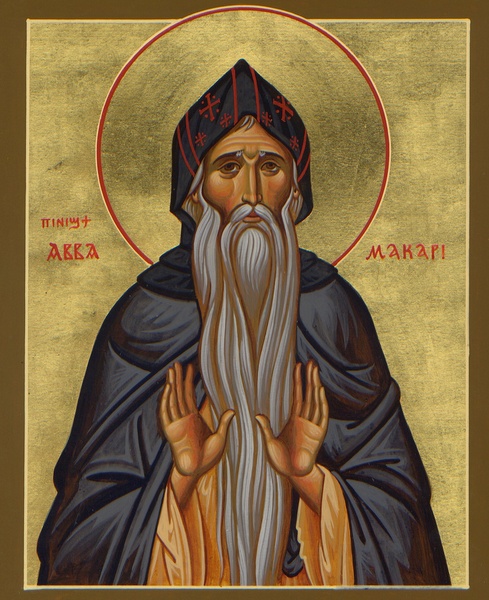

There are plenty such stories from the saints’ lives, but I’ll mention just three. (The first two can be read here.) One involves the fourth-century saint, Macarius of Alexandria, who’s approached by a hyena bringing her blind cub. When he heals it, she thanks him by returning the next day with a skin from a newly killed sheep. He refuses to accept it unless she promises not to harm any other creature, but to eat only what she finds already dead, and if she finds nothing, she can come to him for bread. The hyena bows her head, kneels, and nods, looking at his face. Macarius glorifies God, “who gives understanding to the beasts,” and accepts her gift and sleeps on it for the rest of his life. The hyena, for her part, keeps her promise. Macarius’ likeness to Christ creates a space of heavenly peace and understanding extending to the hyena in her relationship with him, and it lifts her above her instincts as they exist in the world of the Fall, making her more like what she would have been in paradise.

Another story involves the seventh-century Mercian princess saint, Werburga (or Werburgh) of Chester, whose corn is ravaged by wild geese. She tells her steward to order them to follow him and then shut them inside the house. Thinking she’s joking, he goes to the field, and they follow him with their necks bent down. Undeterred by this wonder, he eats one. At dawn, Werburga comes to the geese and reprimands them. But when she dismisses them, they circle her feet to complain about their lost companion. God reveals her steward’s theft to her, and she orders him to bring her the goose’s bones. At her gesture, the skin, flesh, and feathers come to the bones, and the bird rises and flies into the air, the others following it after making paying their respects to the saint. Again, the animals’ contact with God through the saint lifts them above their ordinary natural capacities.

A third story (which can be read on page 122, here) doesn’t have such a happy ending but is just as instructive. The fifth- and sixth-century monk, Sabas of Palestine, heals a lion by pulling a splinter from its paw. The lion becomes a part of the monastery, and Sabas’ disciple Flavius takes it with him on errands to guard his donkey. But one day when Flavius goes into the city, he falls into sin, at which point the lion eats the donkey. This story illustrates the dependence of animals on humans for the restoration of the God-intended order, just as they depended on humans to preserve it in the first place.

Dominion as illustrated in these saints’ lives is characterized by compassion but not irrational sentimentality, use of animals but not selfish exploitation, and command but not arbitrary tyranny. We see humans being what they’re meant to be because of their conforming to Christ. This allows animals to be what they’re meant to be through obedience to these saints. Grace and peace flow from God through the Christ-centered human to the rest of creation, but if the link of human obedience to God is broken, the harmonious order of the animal world is overturned.

These stories, and many others like them, should lead us to rethink what we’re doing when we justify our uses of animals with recourse to “dominion.” Both Genesis and the lives of the saints show that we may use animals for our needs, but also that animals aren’t mere instruments but creatures with their own unique place in the world and their own capacities to respond to their Creator. This is why the saints show them God’s love and mercy. Against their examples, we might ask ourselves what place the modern factory farm, for example, has in an ethos of true Christian dominion. Is this institutionalized abuse of animals necessary for meeting our nutritional needs, or is it more of a catering to our passions that keeps animals from being what they’re meant to be because we’re letting ourselves off the hook from being what we’re meant to be? And how does this sort of practice image the dominion of a God whose power is manifested in weakness, whose authority is manifested in service, and whose love is manifested in self-sacrifice?