NM 6:22-27

PS 67:2-3, 5, 6, 8

GAL 4:4-7

LK 2:16-21

One of the themes emerging from this week’s readings is names, and the task of naming. In the gospel, Jesus is officially given his name at his circumcision. The first reading commands us to invoke God’s own name and receive God’s many blessings. The epistle reading names us as children and heirs of God rather than “slaves.” And we celebrate a particular name that Christians give to Mary – Mother of God.

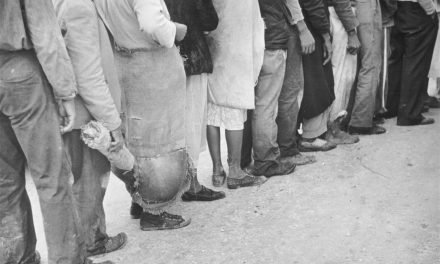

Of course, we know names matter a great deal. Parents agonize over what to name their children – it is their very first, and usually the most lasting, gift to their children. Names bear the marks of parents’ values and concerns, but also whole histories. Children might be named after family traditions (in my family, there is a tradition of boys having “Wesley” as a middle name, after the preacher John Wesley, who preached often in the region of England where my ancestors originated…) They might also be named after saints or virtues, or favorite characters in novels, or freedom names that are not linked to a past of slavery. Parents pore over the meanings of names – and sometimes give as unique a name as possible, in the hopes of emphasizing a person’s individuality.

Jesus’ name is decidedly not unique. It was quite common in first-century Judaism, and means “God saves,” the name the angel Gabriel commanded his parents to give. Jesus’ name is just one more of the many things that emphasizes how radical God is, to have sent us a Son to be among us, to be among quite common folk. He could have been named something like “He-Man, Master of the Universe.” Indeed, if humans had been responsible for naming him, perhaps that is what we might have named him – something that would stand out, make us take especial notice.

To do so would have created a sharp dividing line, though – an us versus God. Not that such a line doesn’t already exist – but to emphasize that line in the person of Jesus defeats the point of the Incarnation. The point is this: God sends his only begotten Son, empties himself, taking the form of humanity, is the Word who dwells among us. God calls us to become friends with him, to be divinized, to be caught up in God’s own life. Us versus God prevents us from seeing Jesus – this radical act of God’s love – for what he is, fully human and fully divine.

To celebrate Mary, Mother of God, is to emphasize the extraordinary ordinary person that is Jesus. The Eastern Church has been naming Mary Theotokos (God-bearer) since at least the fourth century. The name of Mary was the subject of some controversy in those early centuries (well, and later on, too….) – could we name her the God-bearer, or was it more proper to name her merely the “mother of Christ.”

To us, it seems like a very small difference, a matter of names that (to us) mean pretty much the same thing, so can’t we all just get along? My students always protest at my correction of what seem to them to be small errors of naming on exams – since it all just means the same thing anyway, right? (For example: the difference in homoousios and homoiousios, in which there was, indeed, only one iota of difference – so small that my students always look at me in perplexity when I try to explain).

Yet, the names are important. People who argued against “God-bearer” felt that naming Mary “Theotokos” gave too much emphasis to the human act of childbearing, made the Godhead seem too much infused with human birth – but human birth is not a proper part of God’s life. To say “mother of Christ,” however, was a more fitting title that kept the divine and human aspects distinct. Yet bishops like Cyril of Alexandria emphasized the union between God and humanity, equally and completely, that existed in Jesus.

The names we give Mary make a difference, for what we say about her points us toward what we believe about Jesus Christ. Is he fully God, fully human, scandalously brought low into humanity in order to raise us up? Christians say so, however scandalous that might be. And we say so precisely because we do believe that God scandalously also seeks friendship with us, even with us mere humans who fuss, and sin, and do crazy-stupid things. Yet God still seeks us out.

The emphasis and importance of naming has a crucial bearing on moral theology – partly because the way we name our virtues, sins, and activities affects our ability to see our own errors and become better people. It is also partly because the aim of moral theology is to point the way toward our home and friendship in God. If we do not name God and his mother rightly, we shall have a very hard time seeing things clearly enough to know the way home – for we shall find our path blocked by He-Man.

On this, the Octave of Christmas and the feast of Mary, Mother of God, let us celebrate God-with-us, and his ordinary-extraordinary name Jesus, his Mother’s name, and the name that God, consequently, longs to give to each one of us.