Lectionary: 7

- Isaiah 35:1-6, 10

- Psalm 146

- James 5:7-10

- Matthew 11:2-11

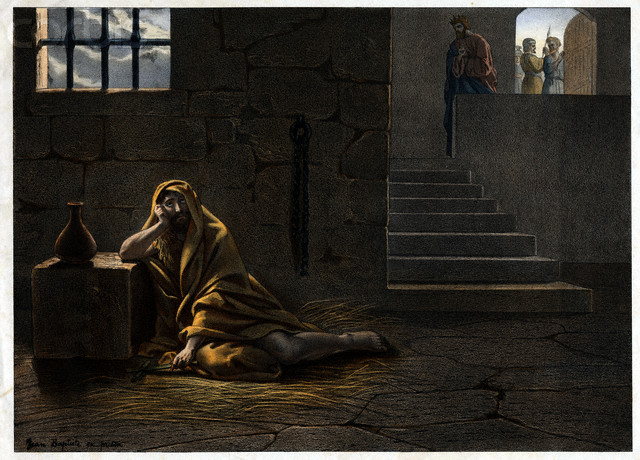

As we enter the Gospel narrative for this third Sunday of Advent, we find John the Baptist waiting in prison. What a powerful image! Jesus says of him that “among those born of women there has been none greater than John the Baptist.” He is the one of whom the Lord spoke through Isaiah: “Behold, I am sending my messenger ahead of you;he will prepare your way before you.” And yet we find him here waiting, wondering, and even perhaps doubting whether all his life’s work has been worth it in the end.

Presumably John heard about Jesus’ activity through his own disciples, who must have been able to come and visit him. In the midst of his waiting, John must have enjoyed this consolation of his friends’ presence and the “news updates” they provided. How intently he must have thought and prayed about all that they told him about all that was happening in the world, and especially about what Jesus of Nazareth was doing! At last he can wait no longer, and so he sends his followers to Jesus with the question: “are you the one who is to come, or should we look for another?”

Offhand I do not know whether any of the Church Fathers interpreted this passage typologically, but it certainly lends itself to such a reading. In the traditional Byzantine icon of the resurrection, the Risen Lord stands atop two unhinged doors, grasping Adam and Eve by the arm and pulling them out of their graves. Beneath the broken doors—the doors of Hades—lies the bound and writhing figure of Satan, surrounding by a myriad of angular metal devices: the shattered locks, shackles, and manacles of those who had been bound by death. The message is clear: death is a prison, and Jesus Christ has liberated those who were held captive by it. With this image in one’s mind, then, one cannot help but hear broader echoes of salvation history in this account of John the Baptist waiting in prison. In a sense, all of us find ourselves in John’s position: bound and burdened by our many limitations, misfortunes, and fears. We struggle to hope in the face of the haunting prospect that all we have been and done may amount to nothing once we are gone.

Held captive, with little hope of escape or release, John cannot help but ask: “is He the one I have been waiting for, living my life for? Is He truly the one whose way I have been preparing, whose salvation I have been foretelling to those who have come to me for the cleansing of their sins?” One wonders what John was hoping for in this situation, what he was really expecting of “the one who is to come.” His followers go to Jesus and ask him John’s question, and receive this reply:

Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind regain their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have the good news proclaimed to them. And blessed is the one who takes no offense at me.

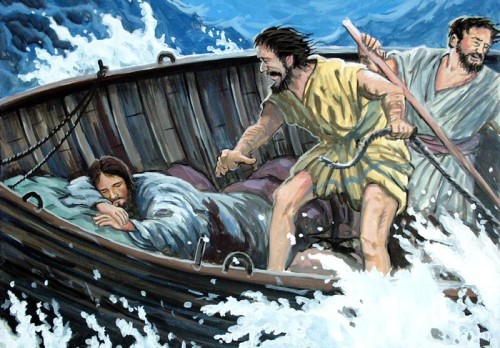

As is typical, the Lord does not answer with a direct “yes” or “no,” but rather launches into a description of his work taken directly from Isaiah’s account of “the time of salvation.” Jesus is bringing about the physical, psychological, and social wholeness of those he encounters. The promised salvation is thus unfolding in the world, coming to fruition not through any cataclysmic cosmological or political transformation, but by the healing of individual persons and concrete relationships. It is slow work, for Jesus must look into people’s eyes, touch them, and speak to them one by one. And yet as all these things are happening, John waits in prison.

Most interpret the last sentence of Jesus’ reply as a rebuke of John. The presumption is that John asks for confirmation of Jesus’ messianic identity out of some measure of doubt or impatience at the seeming lack of effect Jesus seems to be having in the world. “How come I’m still in prison,” he very well may have wondered. Whatever his expectations were for Jesus’ emergence onto the public stage, Jesus seems to have fallen short in John’s eyes. Elsewhere in the Gospels (Jn 3:30), John the Baptist explicitly recognizes that at this point, once Jesus has begun His public ministry, his prominence and influence must give way: “He must increase, but I must decrease.” Here in Matthew, however, we find a much more ambivalent and apprehensive portrayal of John. And so Jesus both admonishes and consoles John with this promise: “blessed is the one who takes no offense at me.”

John’s work as a prophet in the wilderness is now done. He has done his part; he has remained faithful to his mission. He has “prepared the way of the Lord.” And his reward? Incarceration, and eventual martyrdom. It is understandable, then, that he wants to know that it has all been worth it. He wants confirmation that salvation is indeed at hand, even if it there seems to be little of sign of it from where he sits. Who of us cannot empathize with John? What mature Christian has not experienced moments when one must ask the Lord: “Where are you? What are you doing? Are you really who you say you are?”

One cannot help but compare John’s situation to that of Moses on Mt. Nebo, looking over at the Promised Land, which represented the ultimate fruition of Moses’ life’s mission. He can see it from afar, but he himself cannot enter it nor enjoy its fruits; Moses must be content merely to look. He must be content with the promise that the Lord will finish what He started, in His own way and in His own time. So it is with John: he has led his people to their salvation— the Promised One— and now he can only wait and watch from the prison cell of a corrupt puppet king for the “dawn from on high” to break.

Yet such is the condition of every one of us: we are all called to work long and hard in the hope that we might fulfill our own roles in God’s providential plan. The hope of God’s reign and fullness of salvation moves us to give all that we have to this task. Such a hope is a source of profound freedom and joy, but at the same time we cannot forget that we remain in a state of captivity as we wait for this hope. A new world begins to emerge as the old one dies, but the appearance of the power structures and dynamics that have hitherto dominated human life remain unchanged. John hopes in the Lord, but he still waits in prison.

As the first reading for this Sunday so vividly displays, even in this state we must never in any way temper our expectations of the wholeness and healing for which we wait. All indeed will be made well. Every tear will be wiped away, and every wound will be sanctified. But we must still wait for these things to come about, and above all must not take offense at the author of these gifts on account of the manner in which He gives them.

As the second reading from James reminds us, the salvation of the Lord is real and already present among us, as a seed planted within fertile soil. Like the farmer, we must be patient and wait for the seed to grow in its own way according to its own nature. “See how the farmer waits for the precious fruit of the earth, being patient with it until it receives the early and the late rains,” James writes. “You too must be patient. Make your hearts firm, because the coming of the Lord is at hand.”

Patience. Constancy. Forbearance and long-suffering. These are the virtues of one who truly hopes, and who even now enjoys an abundant foretaste of the joy and gladness promised to us. Yet to live in hope is also to wait, and often to wait in captivity, in a place where we can do little to effect or confirm the full transformation we anticipate. However, we must always do what we can; and just as was the case for John, we must rely upon the company of friends and the consolations they mediate to us. Hence open communication is also an essential part of hope. There can be no true hope without calling upon the Lord in prayer.

It was because John hoped so deeply that he sent his followers to the Lord with his question. Jesus’ response that John not take offense at Him may be an admonishment, but it is also an act of communication and above all a renewed link of friendship . It amounts to the simple yet profound exhortation: “trust me, my friend. It will all be worth it in the end. Be patient. Make your heart firm. Wait with hope, for what has been promised is near at hand. Indeed, it is already underway.”