In some ways, the story which prompted this post is nothing new. We have been helping sick children to die (even if one does not think of the fetus as a child) in the developed West for some time. The Groningen Protocol, which has been around for the better part of a decade, outlines with great specificity the circumstances in which the Dutch may actively kill a newborn child. I’m looking forward to exchanging with first author of the NEJM article cited above, Eduard Verhagen, about these and other manners at the annual meeting of the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand this April. Though I obviously think that the protocol is fundamentally wrongheaded, I can understand why some are at a loss to figure out why so many oppose it. After all, don’t we aim at the death of infants all the time by refusing treatment or stopping treatment? Catholic moral theology, of course, considers euthanasia to consist of either an act or omission that aims at death–but our broader Western culture, at least in the law, sees a distinction.

But the Groningen Protocol only deals with circumstances in which a newborn infant is deemed sick enough to be killed; it says nothing about older children. I put this question to Verhagen’s co-author Pieter Sauer at a conference on neonatal ethics at Strasbourg about three years ago. I said that it looks strange that only certain children are eligible for the Groningen Protocol–almost as if older children have a higher moral status than infants such that the latter are able to be killed while the former are not. “Why aren’t older children eligible to be killed in the Netherlands?” I asked. Sauer’s response was consistent, but telling. He essentially said, “We’re working on it.”

As far as I can tell, the Netherlands has not yet come up with a protocol for older children; but today I came across a story that Belgium is trying to pick up the slack:

Medical experts gave evidence to the Belgian Senate on Wednesday as the country’s upper house mulls giving children the right to die. Euthanasia has been legal in Belgium since May 2002, but under very strict conditions. Under the current law, adults who suffer from a serious and incurable condition can make a voluntary and written request to die if they are in a “hopeless medical situation.”

Professor Dominique Biarent, who heads the intensive care unit at the Queen Fabiola Children’s University Hospital, told euronews that the law should be changed. “Some children need to have an answer to their demands because they are suffering so much. They are asking for this,” said Biarent.

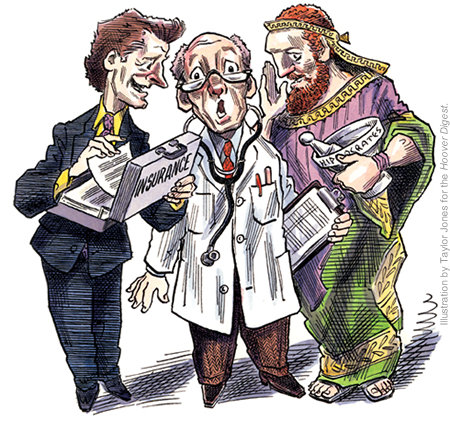

There has been a mountain of response literature to euthanasia in general–and to the Groningen Protocol in particular–but far less has been written about euthanasia of children who are older than infants. There has, however, been a lot of thinking about child autonomy and how it might (if at all) relate to parental autonomy and the interests of the state. We have spent some time on this blog explaining how making various kinds of choices available, far from promoting freedom and flourishing, actually enslaves people to the structural injustices in light of which those choices must be made. Euthanasia, even more traditionally practiced, is precisely one of those choices. In a culture that worships pleasure and capital production–and finds it uncomfortable to look at sickness, pain and weakness–making it easier for vulnerable populations like the infirm, sick, and expensive to kill themselves is a terrible idea.

But putting yet another vulnerability into the mix–being a child–makes this idea truly horrific. Children, and especially young children, do not have the experience or maturity to balance the good of their lives vs. the pain that they are feeling. They do not have the experience or maturity to think about whether they want to live this way or that way in the future–or if they would rather die. These decisions would have to be made by parents and state officials who have interests shaped by the gods of the developed West–especially avoidance of suffering and capital production.

Given the slippery slope down which Belgium has already been sliding, it is difficult to see how this could end well.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks