March 10, 2013

Fourth Sunday of Lent

Jos 5:9a, 10-12; Ps 34:2-3, 4-5, 6-7; 2 Cor 5:17-21; Lk 15:1-3, 11-32

Lent marks one of the (usually) few times during the year that we connect our practices of eating with the practice of our faith. In addition to those who give up chocolate and candy – or other manner of dietary deprivation, we are called to fasting at the beginning and end of the Lenten season as well as abstinence from meat on Fridays. One moral concern is that a fastidious obedience to these restrictions can easily miss the point. Indeed, we are frequently reminded of Jesus’ words: “It is not what enters one’s mouth that defiles that person; but what comes out of the mouth is what defiles one” (Mt 15:11).

But there are other moral implications of our practices of eating. This coming Sunday’s readings, full of the imagery of food and meals, draws us into a contemplation of not just what we eat – but how and with whom we do it.

The first reading offers a subtle suggestion that we may be able to taste the very mercy of God. God removes the reproach of Egypt and the Israelites finally eat of the produce of the land. In this transition from manna to “eating locally,” the Israelites live out the refrain of Psalm 34: “Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.” Yes, we are called to gratitude when we eat. But even more, we should recognize the way in which we literally consume and imbibe God’s providential mercy. What does God’s goodness taste like? If we don’t know, perhaps we ought to take more care to notice.

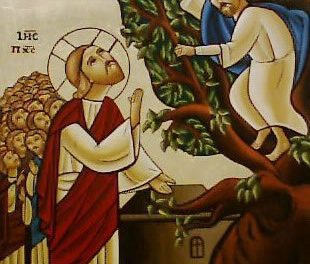

After reading this Sunday’s Gospel story of the prodigal son, we might guess that God’s mercy tastes a bit like the fattened calf. But really, it all depends.

The Gospel passage from Luke begins with a complaint about those with whom Jesus ate his meals: “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.” The story of the prodigal son is the response that Jesus offers. Who we are willing to eat with is vitally important for the Christian moral life. It’s both a literal and figurative test to how well we attempt to live out the inclusive love of God. It’s about who we care to nourish in our community and whether we think they are actually part of our family. Ever since the grade school cafeteria, it has been difficult to reach out to the outcast. If we look around our dinner tables at home and our altar tables at mass, have we made any progress?

As Christian ethicist Laura Hartman notes in her article “Consuming Christ: The Role of Jesus in Christian Food Ethics,” Jesus was “particularly interested in transcending the dietary restrictions that served to separate people from one another.” One way to read the prodigal son is to focus on the divisions created around the feast of the fattened calf. The prodigal son came home because he was hungry; the swine were eating better than he was eating. While he just wanted food, what he received was a meal, a feast. He was received back into relationship and given a place at the table. The older son is indignant at his father’s extravagant smorgasbord of mercy: “…you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends. But when your son returns who swallowed up your property with prostitutes, for him you slaughter the fattened calf.” Notice how he refers to “your son” rather than “my brother.” This complaint is not simply about misallocated generosity but an account of a severed relation. The older son envisions a separate table. But whether a young goat or a fattened calf, eating just among one’s friends is an obstacle to tasting the mercy and goodness of the Lord. And so, in the father’s response we hear a crucial correction to the older son’s assessment of the situation: “But now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.” Despite the prodigal son’s failings, he was to be regarded as brother. The relationship was not to be revoked. This was the condition for the feast.

How and with whom we eat makes all the difference.

As we prepare for Easter feasts, we may need to think about what God’s mercy tastes like. And to do that, we can’t eat the fattened calf among friends. We have to go out to those who are suffering – even those who are culpable for some of that suffering – and call them brothers and sisters. And really mean it.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks