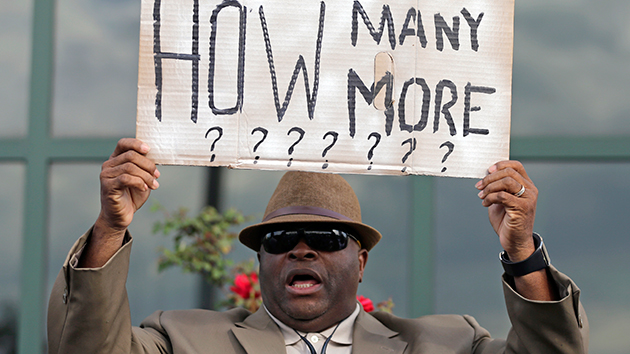

It is something of a banal truism that technology has forever chanced our capacity to see things. With cameras virtually everywhere (on police officers bodies, our phones, millions and millions of city streets, etc.) there is little going on today that cannot be captured with video. And with social media, there is little captured with video that cannot be widely shared and enter the public consciousness almost instantly.

However, we now also have more control over what images we are forced to confront. The logic of The Big Sort leads us to look away from–or, perhaps better, never encounter in the first place–images that make us deeply uncomfortable. Especially when they don’t fit our preferred narrative. And especially when they are connected to unjust violence.

How many who would prefer to tell a different political story have drunk in the terrible video of the shooting of Walter Scott in South Carolina?

What does it say about France that they can ban videos of happy children with Down syndrome merely because such images would force them to confront the massive violence such children face in that country?

What about the willful ignorance present in so many of us when it comes to the readily-available videos of horrific mistreatment of non-human animals, even in zoos?

Yes, technology gives us access to the reality of unjust violence like never before, but a parallel rise in the ability (and tendency) to sort ourselves into real and virtual communities makes it possible (and even likely) that we are not really confronted with said violence.

This is just one of many different kinds of reasons it is important to be part of real and virtual communities that have genuine political and intellectual diversity. If we are not part of such communities, we risk being confronted only with a (often misleading) part of the story when it comes to unjust violence directed at vulnerable populations.

Hey Charlie,

I felt compelled to comment with your mention of the Scott case, which I have been following closely since my parents and brothers are all police in the area. It is a complicated story, and even if we do confront the images, which are awful, we also need to be cautious of drawing overly-simplistic conclusions like “That officer was a tacit racist and look what happened.” Technology may tempt us to turn a blind eye at what we don’t want to see, but it also tempts us to think briefly and superficially based on only a cursory understanding of the issue at hand. You know how I feel about zoos, but there is another complicated story. It isn’t that zoos are simply good or evil. It isn’t that police officers who shoot black people in the back are simply cowardly racists. One of the things we are doing here at the blog is helping people move beyond superficial judgment to think on a higher, subtler, more complicated level. Our tone is one of understanding of all sides with appreciation and mercy towards those who think differently because we know our opponents have much to teach us. I know you agree with all this but I thought it deserved pointing out.