Isaiah 45:1, 4-6

Psalm 96

I Thessalonians 1:1-5

Matthew 22:15-21

One of the greatest challenges I have encountered teaching American university students is getting them to seriously entertain the view that theological and philosophical views might meaningfully correspond to or be constrained by objective reality. Most seem to take it for granted that objective fact is the sole provenance of the natural sciences, and that the conclusions of any other academic discipline, while employing evidence and logical argument, are ultimately the formation and expression of one’s own particular view of the world. This tendency displays itself with particular clarity in the theology classroom, and above all in discussions of moral theology.

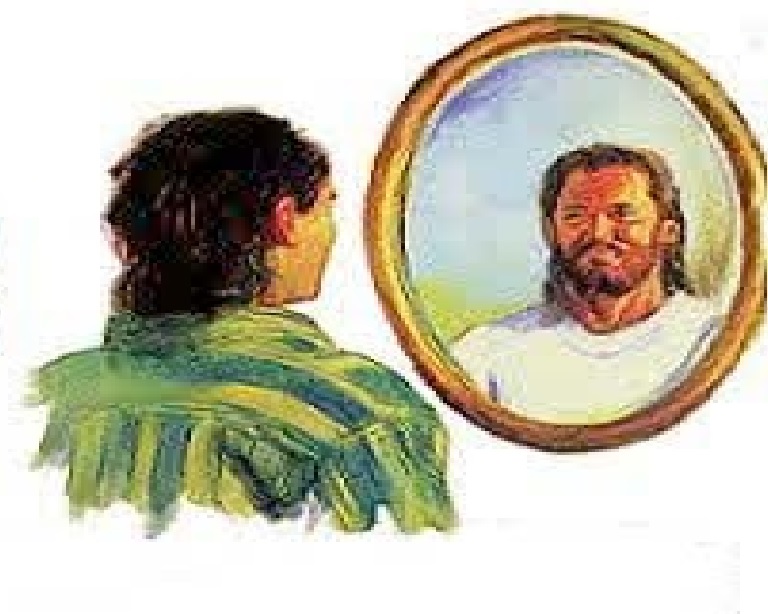

Though a good percentage of my students will interpret Anselm’s ontological argument to mean that “God really exists if and only if we think he exists,” a far greater number of my students take it for granted that the sole origin of moral goodness lies in the individual judgments of human beings, and that the only constraint upon this principle is the sacred immunity of one individual’s judgments from another’s. In my view, this tendency toward what might generally (and generously) be called “subjectivism” carries with it certain advantages and disadvantages, but certainly one of the disadvantages is that it leads one to believe that one only truly belongs to communities and individuals of one’s own choosing. Our life-story, if not the whole of our reality, is the product of our own preferences, attitudes and voluntary associations. Though the deepest core of our identity is self-determined, the image our ourselves which we hold before us may be bolstered, nourished and enhanced by the input of others with whom we voluntary associate, and who in turn voluntarily associate with us. Is this not an apt description of the logic and appeal of the many social media sites that saturate the lives of young people?

For those who live under these assumptions (and I would hesitate to exclude myself entirely from this category), identity is like money and law: its reality ultimately depends upon a critical mass of subjective perception. If enough people opt out of the belief that a currency acts as a vehicle for capital, then it simply becomes the case that that currency no longer acts as a vehicle for capital. Likewise, if a critical mass of people disregard or refuse to enforce a particular legal statute, that legal statute ceases to function as—indeed, ceases to be—a law. In a similar way, does one’s identity dissolve into oblivion without the force of my own (or perhaps others’) self-assertion? Is personal identity in this sense merely a social fiction?

It is to this particular question of moral theology, and to the larger metaphysical questions underlying it, that this week’s lectionary readings speak. In asking Jesus whether or not it is lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, the Pharisees are not just inquiring into the rectitude or prudence of a particular political strategy. They are asking Jesus about the implications of Roman occupation on their identity as a people. They preface their question with flattering words, saying “Teacher, we know that you are a truthful man and that you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. And you are not concerned with anyone’s opinion, for you do not regard a person’s status.” One could read this introduction as a set-up that will more firmly commit Jesus to one side of the debate. Or one could read it through a more contemporary lens as being an ironic disparagement of the very contrast between “opinion” and “truth” in cases like this one. After all, it seems odd to ask about “the way of God” when it comes to something as ordinary as taxes; what does “truth” even mean when applied to tax policy?

The genius of Jesus’ reply is that rather than focusing on pragmatic political strategy, it cuts straight to question of identity and belonging. To whom does this money really belong? And to whom do you belong? We can pay our taxes to Caesar because it is not through this act that we discover and express our true identity. “Repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God.”

Money is a social fiction. We know that. If our identity is likewise a social fiction, then it is perfectly plausible, perhaps even inevitable, to suppose that money plays a determinative role in the construction of who we are. And for many people, money indeed serves this purpose. However, if our true identity lies beyond us—if who we are is not so much a matter of what we choose but rather by whom we are chosen—then it is absurd to think that money and our use of it could make us be anything at all. Money can just be money, and the world can be the world; one’s identity is ultimately found elsewhere.

If membership in the Kingdom of God means anything, it means that we have been chosen to live in a world that is not of our own making. To recognize and accept this gift requires that we acknowledge that our true identity is held by another, and it unfolds in this life precisely through an ecstatic immersion in others. It is not my own self-images or imaginings, but rather the other members of the Kingdom to whom I am entrusted here and now that serve as the key which unlocks who I really am; in my giving to them they give “me” to myself. This capacity for external reference, not merely to an external world but to a way of life completely ordered to “interpersonal externality,” this is the key to our identity as human persons. It is also the defining mark of a son or daughter of God: one who belongs to the God who chose the Persian king Cyrus as the anointed liberator of his people Israel, the God of Jesus who chose Saul the Benjaminite as his apostle to the Nations, the God whose glory and honor is the ultimate meaning of each and every one of us.

Hmmm. Heavy language that basically avoids the issue of money, taxes, collaboration with the empire and the empire’s work. Money can just be money and the world can be the world. Tell that to the poor. Of course it is much more difficult to be a first world Christian if one has to actually live like a Christian in solidarity with the poor as Jesus was. Means you have to take the use of money very seriously. I believe Jesus called the system into question.

Thank you for reading the post, Elena, and for your critical response to it. I think the recognition of the contingent and relative nature of money is indispensable to true solidarity with the poor. Money becomes an idol when people make it more than what it is. Surely you are not suggesting that we pull the poor into the same idolatrous view of money that afflicts the first world, are you? Why didn’t Jesus just say it was unjust to give financial support to the imperial occupation and be done with it? That was the zealots’ view, and clearly one of the positions the Pharisees were hoping Jesus would take. I’d say Jesus’ challenge to the system went even further than that: he relativized one of the Empire’s chief weapons of subjugation. He gave the people a basis for an identity that could resist and ultimately overcome economic oppression.